I’d like to expand the ideas about the 20% Equity Index that I discussed in yesterday’s re-post of one I did back in 2023 after hearing Dr. Ford speak at the NAGC National Convention. In her writing on equality versus equity and underrepresentation in gifted education, Dr. Ford makes one truth unmistakably clear: treating students the same does not guarantee fairness.

For decades, gifted education has relied on equal procedures. The same referral forms. The same tests. The same cut scores.

Yet the outcomes remain predictably unequal.

Dr. Ford’s 20% Equity Index is one of the most powerful contributions to the field because it moves us beyond philosophical debate and into measurable accountability. It gives educators a concrete standard for determining whether gifted programs are equitably serving students from historically underrepresented groups. It is so influential that the Office for Civil Rights has used it in investigations.

This is not simply a statistic. It is a civil rights tool.

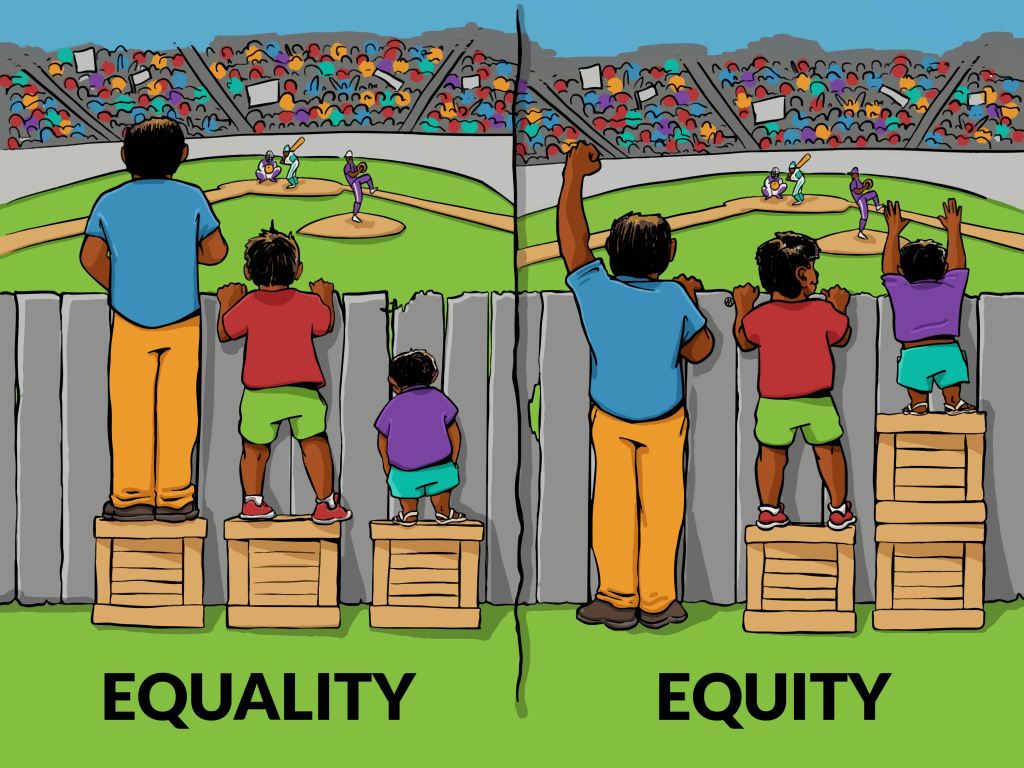

Equality Versus Equity: The Foundational Distinction

In her Equality vs. Equity article, Dr. Ford explains that equality focuses on sameness of treatment, while equity focuses on fairness of outcomes.

Equality asks:

Are all students given the same opportunity?

Equity asks:

Are all students truly able to access that opportunity?

In gifted identification, equality might mean administering the same assessment to all students and assuming the process is neutral. Equity requires us to examine whether the process results in fair representation across racial, cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic groups.

Why this matters:

If a system produces consistent underrepresentation of certain groups, then equal procedures are not equitable procedures. A neutral-looking process can still perpetuate inequity when systemic barriers are ignored.

Dr. Ford challenges the field to stop confusing equal treatment with fair access.

What Is the 20% Equity Index?

The 20% Equity Index establishes a benchmark for identifying significant disproportionality.

A subgroup’s representation in gifted education should be at least 80% of its representation in the overall student population (another way to say this is that each student group represented in a school should also be represented in the school’s gifted program within a 20% margin of the student group’s total school representation). If it falls below that threshold, the program is experiencing inequity at a level that warrants intervention.

For example:

If Black students make up 30% of district enrollment, they should comprise at least 24% of the gifted population to meet the benchmark. If they comprise only 10%, the disparity is not marginal. It is systemic.

The Index transforms underrepresentation from a vague concern into a measurable indicator of inequity.

Why this matters:

Without a benchmark, districts can acknowledge gaps while minimizing their significance. With a benchmark, inequity becomes quantifiable and harder to dismiss.

The 20% Equity Index provides clarity in a field that often relies on general statements about diversity without measurable standards.

Underrepresentation Is a Systems Issue

In her article on underrepresentation, Dr. Ford outlines persistent and well-documented disparities affecting Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, and low-income students in gifted programs. She frames these disparities as structural rather than accidental.

Contributing factors include:

• Overreliance on standardized intelligence tests

• Narrow definitions of giftedness

• Teacher referral bias

• Cultural misunderstandings

• Deficit thinking

• Lack of early talent development

• Inadequate family outreach

These patterns are not about individual students lacking ability. They reflect systemic barriers embedded in identification processes.

Why this matters for real students:

When a gifted students from underrepresented populations are overlooked due to referral bias, those students lose access to advanced curriculum and intellectual peers. That loss compounds over time, and is a travesty.

The 20% Equity Index highlights where these systemic barriers may be operating. Behind every percentage point is a child whose potential may not be fully developed.

Modeling Application: How a Gifted Coordinator Might Use the 20% Equity Index

Here are concrete action steps that gifted coordinators can take to apply the Equity Index to their schools (contact me if you have any questions about this since I’ve been using it in my division):

Step 1: Conduct an Equity Audit

Calculate subgroup representation in overall enrollment and in gifted programs. Apply the 80% benchmark to each student demographic group for race.

Present the data clearly and transparently.

Model language such as:

“What does our data reveal?”

“Which groups meet the benchmark?”

“Which groups fall below it?”

This keeps the focus on systems, not individuals.

Step 2: Facilitate Structured Inquiry

Guide faculty discussions around:

- Referral patterns by teacher and school

- Screening practices

- Assessment tools and cut scores

- Access to universal screening

- Cultural responsiveness of identification criteria

Encourage staff to consider how equal procedures may still yield unequal outcomes.

Step 3: Align Practice with Research

Dr. Ford advocates for systemic solutions such as:

- Universal screening

- Multiple criteria identification models

- Local norms

- Early and ongoing talent development

- Professional learning focused on equity and culturally responsive practices

The Index identifies the problem. Research informs the response.

Step 4: Monitor Progress

Recalculate annually. Equity work is not a one-time initiative. It requires sustained monitoring and adjustment.

Improvement should be measurable. If representation shifts toward the benchmark, systems are becoming more equitable. If not, deeper structural changes may be necessary.

Connecting Research to Students in Your Schools

As gifted program coordinators who work across elementary and secondary levels, we understand that identification affects trajectory.

Students identified in elementary school are more likely to access advanced middle school coursework. Those students are more likely to enroll in honors and Advanced Placement classes. Access compounds over time.

When underrepresented students are excluded early, opportunity gaps widen.

Dr. Ford’s work reframes gifted education as part of the broader equity and civil rights landscape. If gifted programming disproportionately serves already advantaged groups, it can unintentionally reinforce systemic inequities.

The 20% Equity Index is a safeguard against that outcome.

In Sum

Dr. Donna Y. Ford’s 20% Equity Index represents a shift from awareness to accountability.

It challenges the field to move beyond equal treatment toward equitable outcomes. It provides a clear benchmark that exposes systemic underrepresentation. It aligns gifted education with civil rights principles.

Most importantly, it centers students whose brilliance has too often been overlooked.

The Index does not accuse. It measures. And in measuring, it invites responsible action.

For gifted educators committed to talent development of all students, the question becomes clear: Do our programs reflect the diversity of potential in our schools?

The 20% Equity Index helps us answer that honestly.

Your Turn

Take time to reflect deeply within your own context:

• Have you calculated subgroup representation using a clear equity benchmark?

• If certain groups fall below the 80% threshold, what systemic factors might be contributing?

• How might equal procedures in your district still produce unequal outcomes?

• What structural adjustments would be necessary to ensure equitable access?

Consider discussing these questions with your leadership team or faculty, and in the comments below so we can learn from each other.

Equity in gifted education is not a matter of intention alone. It is a matter of design, data, and deliberate action.

Dr. Ford has given us a powerful tool. How we use it will shape the future of gifted education. Please reach out to me if you’d like help using the Equity Index! ~Ann