Reflections from a Session with Wendy Behrens, M.A.Ed. and Ann Lupkowski-Shoplik, Ph.D.

At this year’s NAGC conference, I had the chance to attend an excellent session led by Wendy Behrens, M.A.Ed., Gifted Education Specialist for the Minnesota Department of Education, and Ann Lupkowski-Shoplik, Ph.D., Administrator of the Acceleration Institute and Research at the University of Iowa Belin-Blank Center. Their focus was clear: if we want to meet the needs of advanced learners in meaningful and equitable ways, we must think about acceleration not as a last resort, but as a purposeful tool for talent development.

One of the early resources they highlighted is the National Inventors Hall of Fame YouTube channel. It features short documentaries of inductees and is a powerful reminder of what happens when talent is nurtured early and well.

Gifted Education or Talent Development?

Ms. Behrens and Dr. Lupkowski-Shoplik began by addressing an important distinction. Traditional gifted education programs often look for the all-around gifted student, which can unintentionally overlook students with strong and uneven academic profiles. Talent development, however, focuses on nurturing specific strengths. It allows schools to cast a wider net, reach more bright students, and tailor services to areas where a student genuinely needs advanced learning opportunities.

Two Forms of Acceleration

Schools generally think about acceleration in two ways.

Grade-based acceleration, which moves a student ahead one or more grade levels (skipping).

Subject-based acceleration, which advances a student in a specific academic area.

Their session focused on subject acceleration, which is ideal for students who show high ability in one or two domains but may not be ready for a full grade skip. Some students may have already been grade skipped, yet still need deeper challenge in a particular area. Subject acceleration gives them access to the right level of content without upending their entire school experience.

Considerations for Acceleration, In General

Let me pause my review for a minute to interject some thoughts about this intervention for highly advanced students. Many people have mixed feelings about acceleration- both whole grade skipping and subject-based (technically, subject-based acceleration is grade skipping, just for one subject instead of the whole grade level). Acceleration is one of the most well-researched areas of gifted education and overall is a successful intervention. Still, in our standards-based teaching reality, it is often hard to grade-skip students. To skip over a whole year of standards in one or more subject areas can create holes in the student’s learning. It takes a very carefully crafted Acceleration Plan to help the parents of the accelerated students know what their child is skipping so that they can fill in the gaps for him or her.

In cases where I support schools that are considering acceleration for a student, I first ask them this simple question that I learned many years ago from Dr. Joyce VanTassel-Baska while earning my Master’s degree and Gifted Endorsement at William & Mary: Is the teacher having to differentiate above-grade level for every single thing being taught? If so, the child might be a candidate for whole-grade acceleration. If this level of differentiation is happening in only one or two subject areas, then the student may be a candidate for subject acceleration. The Iowa Acceleration Scales can help the Acceleration Child Study Team at the school make the best decision for the student in these cases.

For students who need more challenge and differentiation and who are not candidates for whole-grade or subject acceleration, it is likely that one of the other 18 forms of acceleration can help meet their academic needs. The types of acceleration that have worked very well in my school divisions over the years are: compacted curriculum, telescoped curriculum, Advanced Placement courses in high school, Dual Enrollment courses in high school, and graduating early from high school by taking extra classes in the summers. The Acceleration Institute at the Belin-Blank Center has a wealth of information and research about acceleration if you’d like to learn more about this topic. Now, back to my review…

Why Subject Acceleration Works

The presenters described several advantages of subject acceleration.

- The classroom teacher does not have to hunt for advanced materials.

- Students are more likely to learn alongside intellectual peers.

- Students earn credit for the work they complete [if they are accelerated to high school-level courses].

- Students stay engaged because they are finally working at the right level.

This approach supports students with uneven academic profiles and helps prevent the boredom, underachievement, and school disengagement that can develop when bright learners sit through repeated content.

What Schools Need to Consider

Successful subject acceleration requires thoughtful planning. Schools should account for scheduling, transportation, credit and placement policies, and long-term trajectories. A student advanced in math today may need access to college-level coursework before high school graduation. These decisions work best when they are made with a long view. Once again, the Acceleration Institute has many resources about acceleration that would be helpful for school divisions.

How Do We Identify Students Who Need Acceleration?

Ms. Behrens emphasized that parent, teacher, or student nomination is not enough. An equitable system includes universal screening and multiple data sources such as:

- grade-level achievement tests and subtest patterns

- end-of-unit or end-of-year assessments

- above grade-level standardized testing two or more years ahead

- teacher observation and rating scales

- review by a team rather than a single individual

Minnesota uses the statewide MCA tests as one data point, but they are designed as a check on school performance, not student-level readiness. Many states might also have state-level achievement assessments such as these. Schools must look beyond them to build an accurate profile of need.

A Framework for Placement and Planning

The presenters shared a clear procedure for acceleration decision-making that schools can follow.

- Review the student’s academic profile.

- Evaluate readiness using mastery data and social-emotional considerations.

- Collaborate across roles. This includes the gifted specialist, administrators, current teachers, and receiving teachers [the school’s gifted specialist MUST be a part of any team studying acceleration as a student intervention].

- Develop a written acceleration plan with goals, instructional settings, and supports.

- Monitor progress with formative assessments.

- Adjust as needed based on student performance and feedback.

- Plan for the long term. Revisit the plan and determine next steps in the talent development pathway.

As I mentioned earlier, many school divisions use the Iowa Acceleration Scales for a thorough, whole-student approach to making decisions about acceleration.

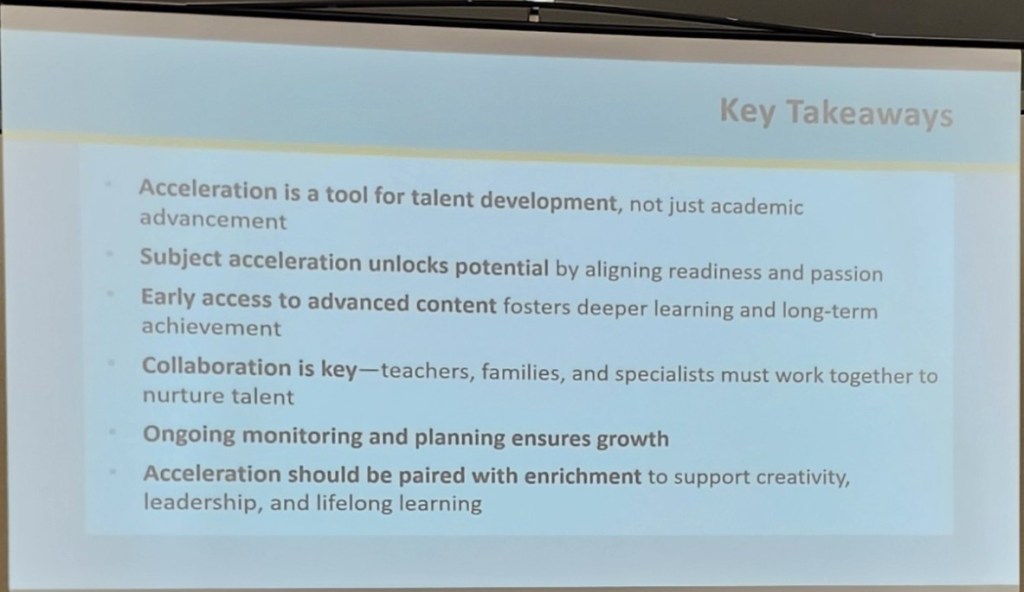

Big Take-Aways for Schools and Families

- Acceleration is an important talent development tool.

- Subject acceleration aligns instruction with readiness and passion, which unlocks student potential.

- Early access to advanced content supports deeper learning and long-term achievement.

- Collaboration ensures better experiences for students and teachers.

- Ongoing monitoring helps maintain appropriate challenge.

- Acceleration should be paired with enrichment for a balanced program.

Ms. Behrens and Dr. Lupkowski-Shoplik reminded us that subject acceleration represents a flexible and impactful way to meet the needs of advanced learners. When done with intention, it can open the door to meaningful growth for students whose talents are ready for the next step.

Does your school division use subject acceleration, or any of the other forms of acceleration? Share your experiences with acceleration in the comments below. Let’s have a conversation! ~Ann

2 thoughts on “NAGC25 Session Review: Using Subject Acceleration to Support Talent Development”