At this year’s NAGC25 Annual Convention, one of the sessions that stayed with me was Dr. Austina De Bonte’s presentation on how a single Washington school district dramatically increased identification of historically underrepresented gifted students. Many of us know the research. Marcia Gentry and colleagues (2019) documented that countless gifted students are never identified, often due to structural barriers in our systems. We also know the best practice playbook: universal screening, local norms, multiple measures and pathways, thoughtful combination rules, high-quality rating scales, and ongoing professional learning. The challenge is that these practices are rarely implemented comprehensively because they require significant coordination and system-wide commitment.

That is what made the Blockbridge (a pseudonym) case study so compelling. This district achieved a sixteen-fold increase in the identification of underrepresented groups. They also increased the overall size of their gifted program by a factor of four. The obvious question is how did they make this level of change possible?

Dr. De Bonte conducted a qualitative study of the Blockbridge School to learn how they increased their gifted identification of underrepresented student groups so well. She interviewed 28 participants, including district leaders, program administrators, principals, and teachers. Her findings were organized through an educational theory framework and fell into three clusters of themes. Three themes were focused on practices, three on outcomes, and three on attitudes that supported the shift.

What Blockbridge Did

Blockbridge redesigned its identification system in ways that were both comprehensive and highly intentional. They implemented universal screening, used static local norms for students identified as low-income or multilingual, created multiple pathways into the program, and adopted OR rules instead of AND rules. One of their most interesting decisions was to create a first-grade NNAT3-only pathway. Students who met this threshold entered a talent pool and were immediately served in the gifted program. The district believed that when children were given the appropriate environment and expectations, they would rise to meet the challenge. The results confirmed that belief.

Their system used two phases. Phase I was universal screening in math, reading, and nonverbal reasoning. Phase II was deeper testing for students who needed additional data. This work was especially impressive in Washington because the state requires only one criterion for gifted identification, yet Blockbridge dug deeper into student data to find students.

Equity Strategies That Mattered

Several deliberate choices helped Blockbridge move their identification rates for underrepresented students so high:

- Screening was done during the school day so every child participated (it used to be done on Saturdays).

- The district implemented operational systems with the precision needed for such a complex process.

- Universal screening occurred in kindergarten through eighth during the transition years while trying to find the best mix of proceses, then continued only in kindergarten, first, and fifth.

- Students could qualify in math only, reading only, or in both areas.

- OR rules allowed students to move forward when any single data point signaled potential (according to Google AI, “An ‘OR rule’ for gifted identification means a student can be identified as gifted if they meet the criteria in at least one of several categories, rather than needing to meet all criteria in a single category).”

- The NNAT3 pathway opened doors for students whose academic scores had not yet caught up with their ability due to opportunity gaps.

Local Norms

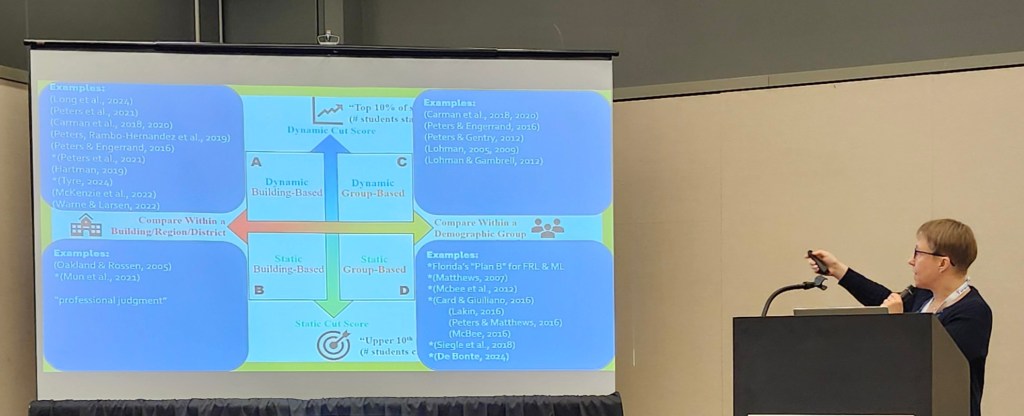

Dr. De Bonte explained the difference between dynamic and static approaches to local norms. Dynamic norms use the top ten percent of students at each school or at the district level, keeping the number of identified students constant. Static norms use fixed cut scores that allow the number of identified students to change. Blockbridge selected static norms that were adjusted for students from low-income and multilingual backgrounds. This decision helped counteract systemic differences in opportunities to learn and was one of the major levers that improved equity.

Matching Students to Services

Blockbridge matched their service model to student needs rather than trying to make identification fit the service structure. Kindergarten and first-grade students received differentiation. In grades two through five, about forty percent of students received in-class differentiation with some math acceleration. The remaining sixty percent participated in accelerated self-contained classrooms. Middle schoolers had access to accelerated sections in core subjects. It was a scalable model that still honored readiness levels.

Professional Development

The district recognized that teachers often rely on personal experience when working with highly capable learners, which can limit consistency. The division actually did very little professional development with teachers regarding gifted identification.

Identification of Special Populations

One of the most notable outcomes of Blockbridge’s evolved gifted identification process was the increase in students identified from special populations including students with Section 504 plans, students receiving special education services, students from low-income households, and multilingual learners. From 2015–2016 to 2022–2023, underrepresented group identification increased sixteen-fold, and overall program participation increased four-fold. The OR rules seemed to boost identification for students with SPED and 504 plans even without static local norms applied to these groups.

Another surprise was how well students performed once identified. Students who qualified via the NNAT3-only pathway performed at similar levels to peers who qualified through traditional achievement-based pathways. In fact, the NNAT3 group was outperforming the achievement group, and none of the identified students were struggling.

How They Made It Happen

Three attitude-based factors emerged as essential.

- Leadership set the direction from the top-down.

- The district worked with an expert consultant and stayed aligned with best practice.

- There was broad support for equity and a shared belief in opportunity and access (Dr. De Bonte reiterated the district leadership’s strong belief in equity multiple times during her session).

Not everything was perfect. As identification numbers grew, some stakeholders questioned the increase. Why were 28 percent of students identified as highly capable? Was this overidentification? Dr. De Bonte reminded us that national research tells us that around 14.9 percent of students are ready for the next level of academic work at any given moment. Many districts are under-identifying gifted students, not over-identifying.

Key Takeaways for School Districts

This was a qualitative study, so the findings are not causal. Even so, the lessons are powerful.

- Universal screening is necessary but not sufficient. Without local norms, districts will miss students affected by the excellence gap.

- OR rules significantly improve identification for twice-exceptional learners [and others].

- Student success data showed that children thrive when placed at their appropriate learning level, including those who entered through non-traditional pathways.

- Rating scales were not used. Blockbridge relied only on objective measures because they are cost effective, easier to scale, and less likely to be perceived as subjective or unfair.

- Major systemic change can be driven from the top down. In this case, widespread buy-in was not present at the start.

- Gifted programs have a moral purpose. Many bright learners already know most of their grade-level curriculum. When school is too easy, they miss opportunities to build learning habits and persistence, and twice exceptional students remain masked.

- A helpful phrase emerged from this work: “Just Right Learning Level.” School should not be too easy for any child. Equity in gifted education is about ensuring appropriate challenge, not rationing opportunity.

Blockbridge shows what is possible when a district commits to equitable identification at scale. The gains did not come from one strategy. They came from a system of aligned practices carried out with clarity, purpose, and belief in every child’s potential. Dr. De Bonte’s session was a breath of fresh air in the equity conversation!

What experiences has your school districts had with gifted identification of students from underrepresented groups? Share them below in the comments. I’d love to hear how other school districts are working on this issue. ~Ann